As we work through Bjorn Lomborg’s massive analysis of 21st century climate policy we come to his discussion of climate policy in general, having last week done the Paris Accord in particular. He introduces this discussion by explaining a basic concept that we could call “economics” but really it’s just simple, obvious common sense. “Climate change has a real cost. But climate policy also has a real cost, and one that escalates as promises and targets ratchet up,” he begins. “From a welfare and a cost-benefit analysis point of view, the important issue is to find the point where the costs of climate plus the costs of climate policy are lowest.” It’s what many economists have spent years doing on this issue, most notably Yale’s William Nordhaus, who won a Nobel Prize in economics for his efforts. (And what, in essence, all real economists do almost all the time.) And the answer they keep coming back to is that for the most part just living with it is a much better plan than blowing up the economy trying to stop it.

Nordhaus, like Lomborg, goes to great pains to insist he’s not a “denier”. He takes all the usual climate model outputs at face value and plugs them into his model. But he doesn’t deny economics either, so he plugs the costs of climate policy in as well. And in fact he could be accused of being overly optimistic since he assumes governments will choose the most efficient policy possible, namely a global carbon tax. But as we saw last week, that never happens, instead governments always choose the most inefficient policies they can, including piling bad policy atop good, and end up doubling or tripling the costs of any gains they do achieve.

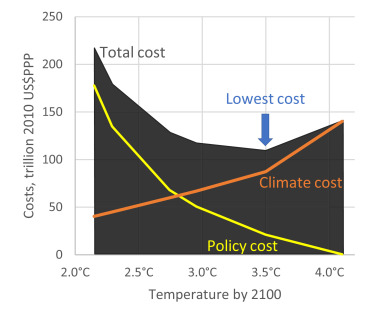

Still, if the alarmist climate models are right and if governments somehow settle on the cheapest possible policy path, where does it get us? In Nordhaus’ analysis, not much below doing nothing at all. Lomborg summarizes the analysis in the following diagram.

The yellow line shows the cost of climate policy (in trillions of dollars) as the limit of acceptable warming goes down. So the point at the bottom right of the graph shows that at zero policy cost, meaning if we do nothing, then according to Nordhaus’ model we will get warming of about 4.1 degrees by 2100. Whereas the upper left end of the yellow line shows that if we try to minimize warming we could get it down to about 2.2 degrees but it would cost $170 trillion doing so. So if we go all in, we spend $170 trillion to avoid 1.8 degrees of warming.

Now to the orange line, which shows the estimated costs of the warming itself. If we keep warming to 2.2 degrees C, the models say the “social costs”, that is, the total losses humans will suffer, would be about $40 trillion, while if we get 4.1 degrees C warming the social costs will be about $140 trillion. Both figures are large, though bear in mind that they should be subtracted from what global GDP is estimated to reach in 2100, which will be enormous barring other catastrophes. But given these calculations, what should we do? From among the available policy choices, which is the best?

The key to figuring out the best option is to add the two costs together, that is, to pile the yellow line atop the orange one, which gives the black area in the chart. Its top line, unsurprisingly, drops initially as fairly cost-effective policies bring significant reductions in temperature increase, the famous picking of low-hanging fruit, and then turns back up as it gets harder and harder to reach more difficult results. And the point where it turns back up, it turns out, is at 3.5 degrees of warming, just a little below the 4 degrees we get from doing nothing. At which point we spend around $20 trillion total on climate policy.

If instead we try to stop the warming altogether, we fail, both in only holding it to 2.2° and in spending so much trying that we pile $170 trillion in policy costs atop $40 trillion in climate costs for a total bill of well over $200 trillion, which is not just worse than the optimum choice, it’s worse than doing nothing at all. So our best bet is to prevent a bit of the warming, but only a little. And if the models exaggerate either the warming or its costs, that choice gets even better.

In fact Nordhaus’ model can be criticized for building in so much climate sensitivity that we get 4 C warming by 2100, which almost certainly is an overestimate. It can also be criticized for assuming politicians will implement efficient policies. Lomborg re-does the analysis under the assumption that policy costs are double the efficient level, and the result is the optimal target moves up to 3.75C, meaning we do even less.

Either way, the conclusion from a mainstream Nobel Prize-winning economic analysis based on mainstream assumptions about the science, rather than the claims of “deniers”, is that we aren’t going to stop warming no matter what we do, and that we shouldn’t try to go to Net Zero or anywhere close. Instead, most targets being talked about are worse than doing nothing, and the optimal policy path involves only modest efforts to reduce emissions over the 21st century. Which actually suggests that all those politicians talking a lot while doing very little are accidentally on the right course.

I wish Lomborg, Pielkie, Koonin etc would just get over the concept of appeasing the climate/insane by saying they accept “the science”. They may as well just admit it’s nonsense and get on with decimating bad policy.

Would the cost of the optimal point be 120 trillion rather than 20 trillion as stated? That does appear to be the level on the graph. Is there a particular reason or calculation for it being 20 trillion rather than reading off the chart?

A moot discussion in my view.No way temps are going to rise 4C above the pre-industrial era by 2100.That is absurd.Just spend money where needed for infrastructure adaptations,for the inevitable natural(and I mean natural!) extreme weather events.And btw all empirical data shows no trend of increasing extreme weather.The computer climate models are most,if not all,wrong.imo

Sometimes (always) I despair that our minister for climate, Bowen, has not read single scientific paper.

Ad he has no brains to know that he would need to read 1000.