This week we begin a series summarizing a major study by Bjorn Lomborg back in 2020 looking at likely trends over the 21st century and the question of whether policies like the Paris target will make us better off or not. (And yes, it sometimes takes us a while to get around to these things, so please get around to sending money for us to hire more staff.) Lomborg holds the view that “Climate change is real and its impacts are mostly negative, but common portrayals of devastation are unfounded.” So we can’t describe him an “alarmist” nor can his critics dismiss him as a “denier”. Well, actually they can and do. They’re like that. But his study draws entirely on data from mainstream groups like the IPCC, the UN and national governments, which should make it even harder to ignore his findings. His bottom-line conclusion is that climate change will likely reduce global income by about 4 percent, but climate policies will have much larger costs. Every dollar spent on the Paris treaty will only generate about 11 cents in climate benefits, making it a wretched investment. This week we begin with the baseline projections: what does the 21st century hold for the world’s population?

Naturally the answer is not a simple forecast, instead it is a set of possible projections. In order to make the discussion manageable Lomborg notes that we need an index that measures how well off we are. He proposes good old income per capita. While economic measures like Gross Domestic Product leave out a lot of what makes life worth living, the fact is that, whatever you think the good life consists of, the more income you have the more likely you can have it. As they say, “Rich or poor, it’s nice to have money.” And statistically, most of the measures of quality of life like health and education and so forth are significantly correlated with income.

What’s more, over a very long time scale average income around the world has gone up dramatically, especially since 1800. As in while human CO2 emissions were rising. But it didn’t happen everywhere at once. Lomborg shows that inequality between nations soared up to the middle of the last century because growth was only happening in certain western countries. Where human CO2 emissions were rising. But once China and other Third World countries implemented free market reforms they too began growing and inequality has dropped. Economists expect it will keep dropping since low-income countries will be growing faster than rich ones.

Lomborg then discusses the dark arts of scenario-building so beloved of the IPCC. Yes, it’s where such gems as RCP8.5 come from. Since they are about to toss out all their work in this area and start over we don’t need to go into detail, but they have a set of outlooks called “Shared Socioeconomic Pathways” or SSPs where IPCC gnomes fantasize about how things will go if the plebs of the world get their way (boo!) or enlightened climate bureaucrats run everything (yay!) and that gives us SSP1 through SSP5. Alternatively you can take note of the fact that surveys of economists indicate they expect global income growth will average about 2 percent per year through 2100, which creates an outlook smack dab in the middle of the SSPs.

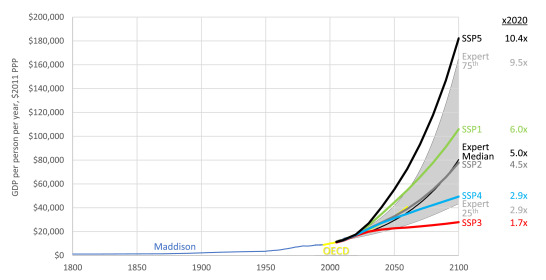

Regardless of which scenario holds, the world gets better off by 2100, as shown in this Figure:

Global income in 2000 was about US$10,000 per person. Under the worst-case outlook (SSP3) it will grow to about US$30,000 and under the best case (SSP5) to about US$180,000, while the median expert projection puts it at about US$100,000. And in all these cases inequality drops so more people share in the benefits.

Of course in the upside-down world of the IPCC, SSP5 is the worst outcome because it involves lots of fossil fuel use and climate warming. But as Lomborg will point out later, even if you tally up the costs of having to adapt to supposed negative effects of the warming, the world is still far better off. In fact if global average income rises to US$100,000 or higher we’ll basically have solved every material social problem that plagued us in the 20th century (except maybe sloth and obesity) and if the price to pay is a milder winter and an earlier start to spring then count us in.

Lomborg then discusses trends in energy use, which is fundamental to understanding growth of income. And there he makes the surprising point that the world isn’t trending towards renewables, we’re trending away. Or at least we have been.

Up to the 19th century the world relied mainly on renewable biomass like wood and animal power. Then coal and oil came along in the 20th century, followed by gas, and displaced the traditional sources. Now wind and solar are emerging, but even the IPCC mid-range outlooks keep fossil fuels as the dominant energy sources through 2100 no matter what breathless hype you may encounter from climate-activist journalists.

So the outlook for the economy based on UN data, IPCC oracles and mainstream economic forecasts is that over the next 80 years the world will get much richer, energy will become much more abundant and global inequality will decline. But there will also be climate changes to contend with. Beginning in Part 2 Lomborg looks at what the experts and their data say the costs are likely to be.

What's crazy is his estimates are based on RCP8.5. In the likely event RCP8.5 ends up being wrong those global income per person numbers look even better.