In an almost misty-eyed look back at 2020, the Guardian’s global environment editor (how many environment editors have they got?) Jonathan Watts waxes lyrical about how the great lockdown, despite doing far too little to save the planet, was a great start in saving the planet. “During the northern hemisphere spring, when restrictions were at their strictest, the human footprint softened to a level not seen in decades. Flights halved, road traffic in the UK fell by more than 70%. Industrial emissions in China, the world’s biggest source of carbon, were down about 18% between early February and mid-March… The respite was too short to reverse decades of destruction, but it did provide a glimpse of what the world might feel like without fossil fuels and with more space for nature…. Alongside apocalyptic images of deserted roads, the internet briefly buzzed with heartwarming clips of sheep in a deserted playground in Monmouthshire, Wales…” Because to a green extremist nothing is more heartwarming than a deserted playground.

Except, perhaps, a deserted city. In images that might have been borrowed from the film version of Logan’s Run, we saw “coyotes on the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, wild boar snuffling through the streets of Barcelona, and deer grazing not far from the White House in Washington DC.” Ah yes. We need to destroy civilization in order to save it.

We should not be too snide. It is true that 9 billion people are crowding nature in potentially disastrous ways, for it and for us, and it would be excellent if we humans could reduce our pressure on ecosystems and live with more nature around us. But it won’t be accomplished by making us poorer and more desperate for the resources needed to survive. It will be accomplished by making us richer and better able to care for the plants and animals around us, and the marshes and rivers and forests and oceans and the cute creatures and the disgusting bugs and so on.

Watts admits it wasn’t all gravy. Thrilled as he was by his own society grinding to a desolate halt, he admits that “In the global south, the picture was more mixed. Rhino poaching declined in Tanzania due to disruption of supply chains and restrictions on cross-border movements, but bushmeat hunting, illegal firewood collection and incursions into protected areas increased in India, Nepal and Kenya because local communities lost tourist income and sought other ways to care for their families.” But if you read the piece, it’s astounding how positive he thinks the lockdown was and how indifferent, even callous, he is about its tremendous impact on people’s livelihoods, their peace of mind and even their physical health.

Indeed, on the latter he thinks being unable to socialize or exercise was beneficial. “Elsewhere, there were health gains, though probably not enough to offset the losses. Providing a little relief from rising Covid death tolls were projections in Europe of at least 11,000 fewer fatalities from air pollution. Breathing cleaner air also meant 6,000 fewer children developing asthma, 1,900 avoiding A&E visits and 600 fewer being born preterm. In the UK, 2 million people with respiratory conditions experienced reduced symptoms. The change was visible from space, where satellites picked up clear reductions of smog belts over Wuhan in China and Turin in Italy. Residents in many cities could also see the difference. In Kathmandu, Nepal, residents were astonished to make out Mount Everest for the first time in decades. In Manila, the Sierra Madre became visible again.” And the losses that he does acknowledge, note carefully, are from COVID-19 itself, not from all the psychological and physical impacts of the lockdown including the devastating effects of loneliness and despair.

Again, we are not praising air pollution. But notice that smog is a problem in poor societies not rich ones, so making us all poorer is unlikely to fix it, unless you make us so poor that coyotes wander the streets and sheep the playgrounds from which humans have disappeared entirely.

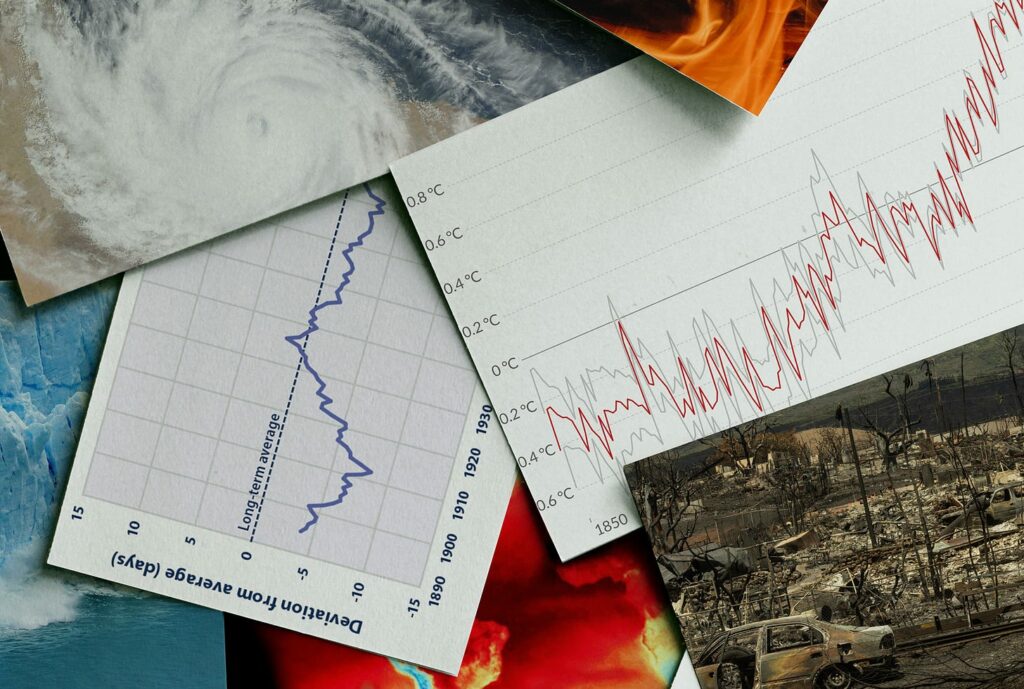

Alas, he notes, the splendid lockdown ended and “the gains were short-lived. Once lockdown eased, traffic surged back and so did air pollution…. The story is equally disheartening when it comes to global carbon emissions, which fell steeply but not for long enough to dent climate fears. Months of empty roads and skies and sluggish economic activity reduced global greenhouse gas discharges by an estimated 7%, the sharpest annual fall ever recorded. That is a saving of 1.5 to 2.5bn metric tons of CO2 pollution, but it merely slowed the accumulation of carbon in the atmosphere, leaving the world on course for more than 3.2C of warming by the end of this century. In its annual emissions gap report, the United Nations environment programme said the impact of the lockdown was “negligible”, equivalent to just 0.01C difference by 2030. On a more optimistic note, it said ambitious green recovery spending could put the world back on track for the Paris agreement target of less than 2C of warming. There is scant sign of that so far.”

So what is to be done? Well, we could have another plague, a more deadly one, that actually killed people on the scale of the Black Death. Or governments could panic and lock us all up for another year because, as Watts warns us amid apocalyptic depictions of hurricanes and typhoons, brushfires, the melting Arctic and Antarctic, “Epidemiologists and conservationists have warned that outbreaks of coronavirus-like diseases are more likely in the future as a result of deforestation, global heating and humankind’s treatment of nature.”

So win-win. For a certain mindset, anyway.