Forest fire scientists use the concept of a “fire deficit” to describe a situation in which, however many fires are observed, there aren’t as many as nature would normally arrange. So with all the discussion of wildfire risk associated with global warming we could ask if there’s a fire deficit or its opposite, a fire surplus. Plot spoiler: while alarmist rhetoric would naturally have you think there’s a surplus, it’s actually a huge deficit. Indeed according to a new study from a team of US and Canadian forest scientists (h/t Roger Pielke Jr.), since 1984 there have only been about 25 percent as many North American fires as there ought to have been based on records of natural wildfire activity from 1600 to 1880. Even our supposedly record-setting years are, by comparison, remarkably calm. The authors do note that some locations are experiencing increasingly intense wildfire events because fire suppression has allowed a large fuel buildup. But overall we have a huge fire deficit compared to the natural fire baseline although, as Roger Pielke Jr. notes, according to the journal peer reviewers you’re not supposed to know this lest the information be used by “deniers.” So when we tell you what the study showed they want you to be vewy vewy quiet.

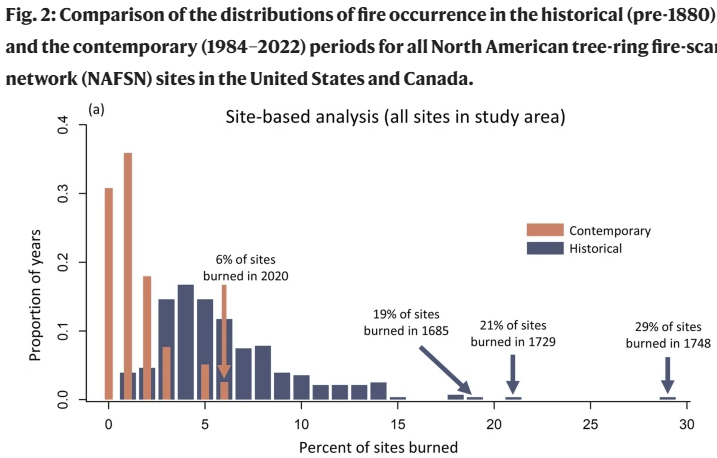

The authors made use of a data set of fire scar records from tree ring samples across North America and Canada to develop an annual record of how much area was burned from 1600 to 1880. That measure allowed them to generate a distribution of fire activity, establishing a baseline of what nature would do in a stable fire-prone forested continent. Then they looked at the record of fire activity from 1984 to 2022 and compared the distributions. And the result looked like this:

The blue bars show the bell curve of natural fire activity while the orange bars show the bell curve of modern fire activity. It is clear that modern counts of fire activity are clustered on the low end, meaning fires are much less common now than in the past. Even our worst years (such as 2020) fall well within the normal range. Referring to the North American Fire Scar Network (NAFSN) locations the authors say:

“Overall, contemporary fires (1984–2022) burned NAFSN sites less frequently than fires during the historical reference period (pre-1880), indicating that a substantial fire deficit persists and is still accumulating across many forests and woodlands across the United States and Canada... Based on the historical fire-scar record, NAFSN sites collectively would be expected to have burned 4346 times from 1984–2022, yet they burned 989 times, or only 23% of what would be expected under the historical fire regime... Recent years of particularly widespread fire activity are not unprecedented when compared to the historical reference period across NAFSN sites in the United States and Canada.”

The authors also observe that wildfire is inevitable, and fire suppression efforts that result in excessive fuel buildup mean the fires will be that much more severe when they start.

“In many western North American forests, particularly those represented by the tree-ring fire-scar sites analyzed here, heavy fuel loads and increased fuel continuity have developed because of fire exclusion, thereby increasing fire severity when forests inevitably burn.”

RPJ’s writeup about the paper includes an interesting quotation from the peer review record (which this journal puts online). One reviewer, incautiously, came right out and said what we often accuse alarmists of thinking: even if the data is correct please consider suppressing it in order to preserve the narrative, and Pielke Jr. quotes it:

“I see this paper as potentially being used by deniers of climate change impacts. Consider if possible some rephrasing here to put even more emphasis on impact rather than on burned area.”

“Rephrasing” being a word here meaning the data are right and imply that modern forest fire rates are not unusual, and since we want people to believe the opposite you need to distort the implications and hope people are too dumb to notice or too complicit to object. We wish we could report that the authors told the reviewer that science does not work that way, possibly in more pointed language. But alas this is the climate science profession so their response was:

“We share the concern that climate change deniers may misuse our findings.”

“Misuse” being a word here meaning quote accurately and interpret correctly. So the authors tossed their integrity into the flames by adding lots of text about how forest fire impacts are still terrible and people need to manage the risk carefully. A contrary finding should be exciting to an aspiring scientist… but climate science isn’t like the other kinds so they tried to bury it to uphold a consensus their own research undermines.

It’s not a direct lie; in fact it’s true and we all knew it already. But it deliberately distorts the finding, generally and also because one of the things that stands in the way of managing forest fire risk is the belief among alarmists that we didn’t used to have forest fires and if only we could go back to preindustrial poverty levels we’d once again be free of the risk. Whereas in reality if we banned fossil fuels we’d have as much or more wildfire activity as we used to with no way to put the fire out or protect the people in its path.

So we deniers will use these results to make the arguments we think make sense, especially that wildfires are a natural part of the landscape, we will always have them and the key is to manage the risk by cutting back forests from near residential areas, reducing fuel loads and making sure that fuel for fire suppression aircraft and rescue vehicles is abundant and affordable for the inevitable day when despite our best efforts a forest fire breaks out.

"It’s not a direct lie;"

Then what the hell is a direct lie?