We continue reviewing Bjorn Lomborg’s detailed examination of likely trends over the 21st century and the question of whether policies like the Paris target will make us better off or not. Plot spoiler: take a guess. This week we bring you Lomborg's look at projected impacts of extreme events like floods, wildfires and hurricanes. Although what he really looks at is the projected impact of people being too stupid to adapt to slow-moving changes. Once we take account of how people adapt, especially when they are wealthy enough, the impacts become predictably small.

Lomborg begins by reviewing what he calls the “expanding bull’s-eye effect”, which simply means that because of major increases in population and prosperity in recent decades (despite the supposed accelerating disastrous impacts of climate change) the same size weather event moving across the landscape today has many more people and much more stuff in its path to aim at. So when we talk about the costs of hurricanes over time, he cautions, it is important to compare apples and apples:

“Consider the Great Miami Hurricane of 1926, which tore through downtown Miami. Because only about 100,000 people lived there at the time, with less costly houses, the inflation-adjusted damage ran to $1.3 billion. However, modeling the cost of the very same hurricane tearing down the same path today would make it the costliest US catastrophe ever, with damage worth $254 billion.”

Lomborg also discusses estimates of the impacts of flood damage over the 21st century, quoting a book that claimed they could reach as high as US$100 trillion annually by 2100, more than today’s entire GDP. Well sure, but that assumes people stand slack-jawed staring at sea level increases and do nothing in response.

If that’s how people are going to behave in the rest of this century, never mind climate change because today’s high tide will drown them. Lomborg points out that:

“because it ignores adaptation, this description exaggerates the problem by up to two thousand times. The misleading narrative is, unfortunately, often encouraged by research that routinely neglects adaptation or treats it as a casual add-on.”

He points to a study that took adaptation into account and, to no one ‘s surprise, found the costs of sea level rise as of 2100 all but disappear, falling from $55 trillion (5.3% of GDP) to $38 billion (0.008% of GDP). But he notes that the media only ever talk about the without-adaptation estimates, again to no one’s surprise.

Moving on to droughts, Lomborg points out that while the IPCC claimed in 2007 that global droughts were increasing, in 2013 they had to retract that claim because the data no longer supported it. So kudos to the IPCC for admitting it, although they sure didn’t go to any effort to let people know they’d had a change of heart in the anti-alarmist direction.

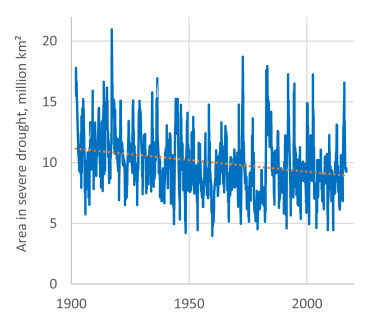

Lomborg reports that actually the area of the world under severe drought as measured by the gold-standard Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) has been declining over the past century, as shown in this chart:

As for the future, only under extreme emission scenarios (yes, the dreaded RCP8.5 again) does that line turn upward, but even then the impacts can be managed by adaptive behaviours.

Next Lomborg reviews evidence on flooding, a topic we’ve covered in many of our previous videos, including a little gem called Pavlov’s Floods which we are very proud of but it only got 13,000 views so click on the link and share it widely so it won’t feel hurt. In short, the IPCC doesn’t claim they are going up except here and there (and going down there and here) but the cost as a percentage of GDP is going down because we’re better at managing flood risks.

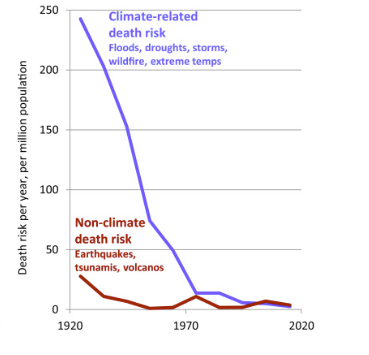

From there Lomborg goes on to discuss wildfires and hurricanes, topics we’ve had lots to say about recently and while his data won’t surprise experienced CDN readers, it naturally goes directly against the supposed mainstream narrative. He concludes by talking about the important notion of resiliency: being able to deal with whatever nature throws at you. The key to resiliency is wealth and prosperity, as proven by the dramatic decline in climate-related deaths over the past century shown in this chart:

Thanks to fossil fuel-powered growth in income, people today are at a risk of climate-related demise that equals only 1% of what we faced in 1920. If this outcome is a “climate crisis” we say send more climate crises.

I cannot support the insurance industry laying the increase in premiums on the mat of climate "change". Hundreds more properties are built in flood or fire borne areas. Why, because we want to live amongst the trees and look at our river flowing past our front garden. Every year the number of people building, in these areas increases, every year their property value increases, every year the rebuilding cost increases. NOTHING TO DO WITH CLIMATE CHANGE

Your numbers in paragraph five don't add up. If the costs of sea level rise, without mitigation in 2100, are $55 Trillion at 5.3% of GDP, then the GDP = $55T / .053 = $1,038T. If, with mitigation, the costs are $38 Billion at 0.008% of GDP, then the GDP = $38B / .00008 = $475T.