As we mentioned last week, the Royal Dutch Meteorological Agency (KNMI) has been forced to admit that they artificially scrubbed historical heatwaves from their temperature records, after a group of analysts with Clintel, the Dutch climate skeptics group, published a report exposing the monkey business. The story is fascinating both for the scientific content and what it reveals about government climate agencies, so we decided to go through it in more detail this week. And indeed the story has all the elements we have grown accustomed to: outsiders doing the investigation neither government nor academic experts could be bothered with, the government using its clout to suppress media discussion of the criticism, then after years of stonewalling quietly admitting the skeptics were right all along.

It began with the usual media claims that heatwaves are much more common now than in the past. This led some data-savvy observers in Holland to question how the KNMI concocted their records. They found that there are only five locations in the Netherlands with long temperature records, a word here meaning reaching back to 1906. Their monitoring systems all experienced changes over time, such as the equipment being moved or replaced. At four of the locations, when the site was moved temperatures were recorded at both old and new locations for a while so an adjustment factor could be computed. But at one of them, De Bilt, parallel observations weren’t made, so the adjustments needed to be computed using comparisons to other locations.

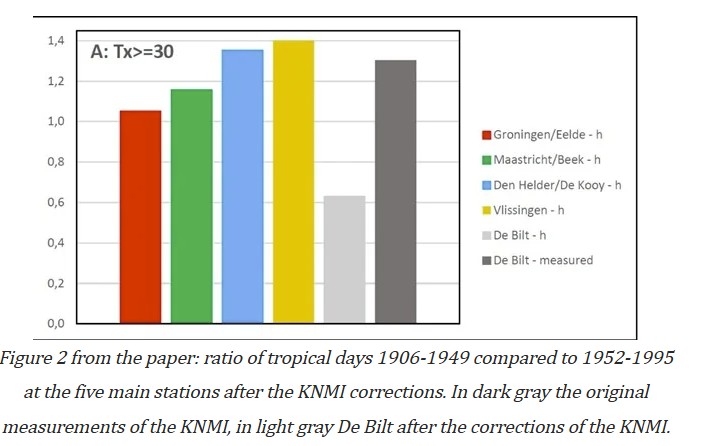

Fair enough. But there were multiple sites to choose from for the purposes of this comparison, and moreover multiple ways to compute the adjustment based on their data. So guess which they chose. Right. Even though the raw De Bilt records showed there were more hot days (>30 degrees C) prior to 1950 than after, KNMI adopted a method in 2016 that resulted in new records showing 40 percent fewer hot days before 1950 than after. And on the topic of which site to choose to get this result, um, no such drop was observed at other sites. It came from outer space or something. Like a dogmatic conviction that it must be so and mere data be hanged:

So the Clintel team began digging into how the adjustment was done. They soon found that there were 116 possible variations of the adjustment method that could be applied, almost all of which would yield around 110 days above 30C over the historical record, but KNMI picked one specific method that dropped the number down to only 76. Indeed, one specific method guaranteed by its internal dynamics to yield nearly the minimum possible estimate out of all the options. More reasonable assumptions would greatly increase the estimated number of historical heatwaves in the Netherlands. But reasonable wasn’t the goal here.

The Clintel team wrote up a report about their work in 2019 and posted it online. And they soon attracted the attention of a Dutch newspaper that began working on a story about it. But the KNMI wasn’t having it. Clintel director Marcel Crok explained what followed:

“An article was prepared for a major Dutch newspaper, but after interference by the director of KNMI, the editor in chief of the newspaper decided not to publish the article. A spokesman of KNMI used ad hominem arguments against us (or mainly me as I am the most visible of us four). After questioning this in an email I had a conversation with the director of KNMI and the spokesman. It was a shocking experience. They told me they wouldn’t response [sic] to our extensive report as they didn’t ‘trust me’. I replied science isn’t about trust. ‘Our report is either right or wrong and in both cases I would like to know’, I replied.”

KNMI took a different view. So after they slammed the door, Crok and his coauthors decided to try to get their work into a mainstream science journal. And to their surprise they succeeded: it was published in Theoretical and Applied Climatology in 2021. Surely, they thought, now KNMI would listen.

Uh, that’d be not. This time a media story did appear and KNMI acknowledged that the analysis was ‘interesting’ but said little else. They promised to look into it. And apparently saw only their own gorgeous reflection, because the years started rolling by with no change or meaningful acknowledgement. But the story has a happy ending, sort of.

As Crok writes:

“Still, 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025 went by and there was no news about it. Meanwhile national weathermen kept claiming on national television that heatwaves are much more frequent nowadays. But many people in The Netherlands were aware of our critique, especially on social media platforms like X, Linkedin and Facebook. Last October, finally, the first author of our paper, Frans Dijkstra, was contacted by KNMI and asked to review their homogenization 2.0. Much to our satisfaction, we observed that the KNMI had in fact recognized the validity of our criticism.”

Moreover this January KNMI quietly changed their algorithm, resulting in a doubling of the number of pre-1950 heatwaves in the record. While the Clintel group thinks that’s still a bit low, it is a big improvement. Suddenly the recent decades no longer stand out as being so highly prone to heatwaves compared to earlier in the 20th century.

Well, about time. But we have to wonder how many other times have outside groups asked legitimate questions about government climate science agencies only to be blown off with insults and censorship. And how often the outsiders gave up in frustration and went away, so the fudged results and cooked data don’t get corrected because the alarmists have all the money and all the time. But not in this case, so we salute the Clintel group for persevering until KNMI finally caved and did what they should have done from the beginning.