Continuing University of Guelph professor Ross McKitrick’s look at Steven E. Koonin’s landmark book Unsettled: What Climate Science Tells Us, What it Doesn’t, and Why it Matters.

A big challenge of climate policy is that it is the stock, or total amount, of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and hence the concentration, that affects the climate. But all we can control is the flow, or annual emissions. And because the stock is so large compared to the flow, the concentration changes very little, and only very slowly, in response even to large changes in emissions. Now add the fact that carbon dioxide emissions are more closely tied to economic prosperity than any other type of air emissions, which means it is very difficult to cut global emissions even by a small amount, and you begin to grasp why global climate policy is, and will continue to be, a costly failure. In chapter 12 of Unsettled Koonin recounts the process by which he came to understand this reality, and his realization that both when he worked at BP Energy and later for the Obama administration, if he said it out loud he’d probably have been fired.

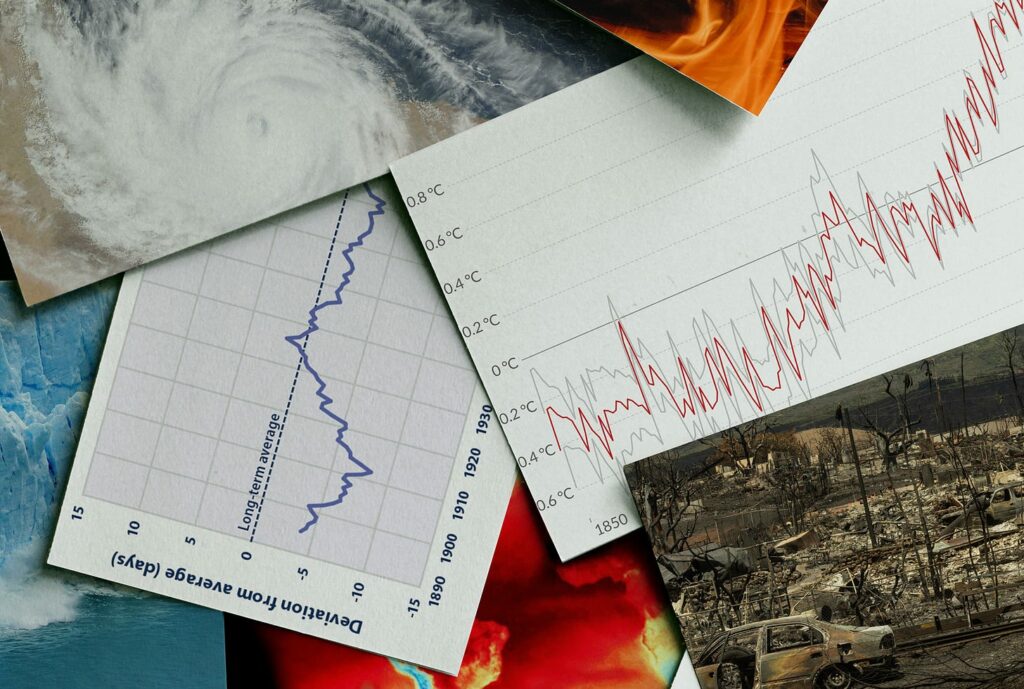

The numbers are undisputable, and the conclusions don’t depend on one’s assumptions about how carbon dioxide affects the climate. Global CO2 emissions have been rising for decades, despite efforts to cut emissions that started in earnest in the 1990s. To stop the global concentration of CO2 from rising further would require global emissions to fall by more than half. Some developed countries (such as the US) have at least temporarily stabilized their emissions, largely by switching from coal to gas for electricity generation, but they haven’t actually cut them. CO2 emissions are unavoidably tied to fossil fuel use, and economic activity depends on energy. There are 5 times as many people in the developing world as in the developed world, and they want more energy. If India attains even the lowest per capita fossil fuel usage levels currently enjoyed by developed countries, global CO2 emissions will rise by 25 percent. Realistic outlooks for global energy use through the 21st century indicate that fossil fuels will still dominate the world energy supply. The Paris Treaty, if fully implemented, would barely change the global CO2 concentration by 2100, and by implication, would have almost no climatic effect. And yet countries are not on track even to do that much.

Partial measures won’t cut it, either. As Koonin notes, if developed countries impose draconian emission reduction policies, the carbon-intensive manufacturing activities will simply move elsewhere. Indeed this has already been happening, so some of the emission “reductions” in places like the US and Canada should more properly be seen as simply relocations, especially to China. Despite the current fondness for promising “Net Zero” by 2050, under current technology it simply isn’t going to happen. We can learn to adapt to whatever changes come to the climate, but we aren’t going to stop them.

Digging further into the topic, in Chapter 13 Koonin looks more closely at the US. What would it take for the US to become carbon neutral? Electricity and transportation infrastructure cannot simply be rebuilt overnight to accommodate a new technology. They change slowly for the same reason the atmospheric CO2 concentration changes slowly: the stock of equipment and technology is large compared to the flow. Koonin points out that the repeated call for a “Manhattan Project” approach to climate change is inapt. The Manhattan Project didn’t aim to transform a large system already embedded in society, it aimed to build a single new gadget for a single client. It also got to work in secret with an effectively unlimited budget: it didn’t have to run its spending plans by the taxpayers each election.

Policy, technology, demographic and economic forces all mean that global CO2 emissions are going to keep rising. The Paris Treaty, with its strange and ambiguous goal of keeping warming to under 2°C (an arbitrary number which Koonin shows is not supported by economics, even if we had such precise control over the climate to make it operational) cannot circumvent the challenges that make it almost certain to fail. Meanwhile, as Koonin notes, we see politicians outbidding each other by proposing ever more ambitious targets 15 or 30 years down the road, long after they will be out of office. Perhaps they too realize that the alternative is to tell the truth, and get fired.

Next week: Plan(s) B