We often hear the charge that so-and-so is not a climate scientist so whatever he says should be ignored. And we often point out in reply that neither are Al Gore and Greta Thunberg. But it doesn’t stop climate activists from hanging on their every word. (Or those of António Guterres or, on climate, the Pope, though they too lack formal climate credentials like the vast majority of climate journalists including those making this crack.) But the other important rebuttal to that charge is that sometimes the analysis needs a different skill set than a PhD in meteorology, climate modeling or even atmospheric physics. And nowhere is it more likely to be the case than when a debate hinges on statistical analysis. In that case someone with a PhD in statistics or econometrics is exactly who you should listen to. Which brings us to a new paper by Rice University economist Dr. Peter Hartley which uses methods familiar to people in econometrics and finance to analyse whether CO2 and temperatures move together over time the way climate theory says they should. They don’t, Hartley finds. Despite what you’ve heard, including from a lot of people with extremely shaky math backgrounds and no corresponding humility, if CO2 really were the climate control knob, temperature data would look very different.

Actually it might look pretty much the same on a graph. But it would look different under the kind of statistical microscope that econometricians use. It’s common to look at data and see if there is an upward or a downward trend. But economists are often more interested in how tomorrow’s value will be affected by events today, which means they want to measure something called persistence. If every day brings something new and unexpected, knowing yesterday’s data including accurately calculating its slope doesn’t help you predict what will happen today. And the same is true if events today depend not on yesterday but dates further back. Especially if random events have effects that persist over time rather than dissipating quickly, knowing how they cast a shadow forward makes for better forecasts. So the people whose livelihood depends on making forecasts have put a lot of work into measuring patterns of persistence.

Some data series show very strong persistence because today’s event, even if unexpected or even impossible to predict from past data, changes the pattern forever. When the steam engine was invented, and especially when its efficiency was dramatically improved by James Watt (venting the cylinders instead of having to cool them on every stroke) industrial productivity changed permanently.

While people would improve on them further in the future, there was no chance that next year they would forget how to make them or blow them all up and go back to mule power or windmills. In technical language, when persistence is strong enough that random changes have permanent effects the data is said to contain a “unit root”. (The reason for this term is that the effect is measured using the square root of a parameter in a complicated formula, and if it has the value 1.0 that implies permanent persistence, hence unit [square] root).

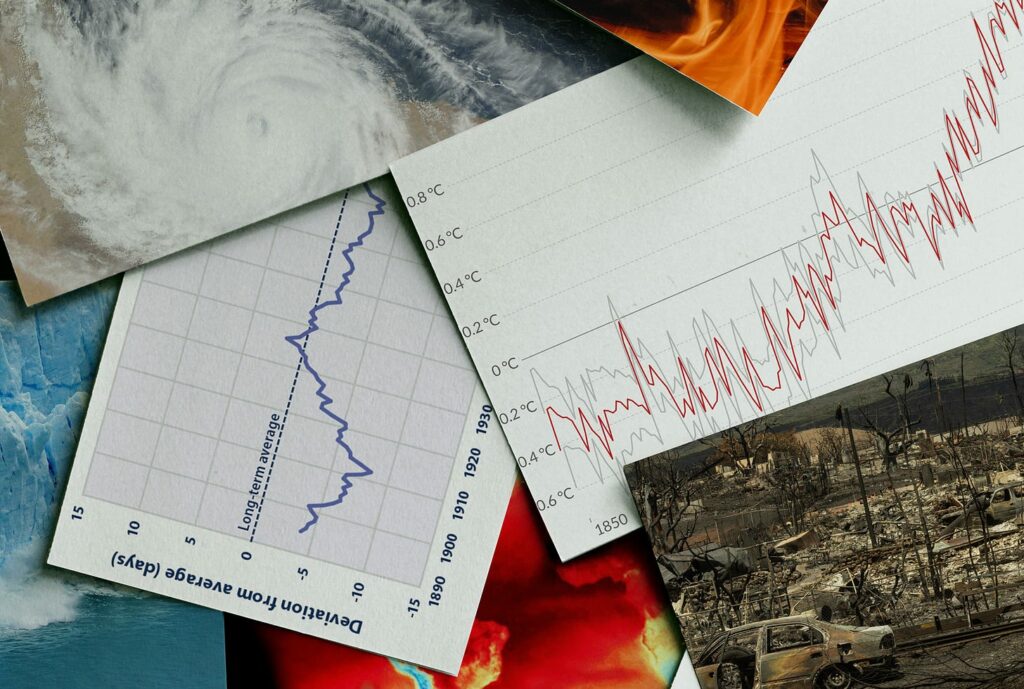

Hartley notes that the simple IPCC control knob model implies that average atmospheric temperatures should track CO2 levels in the atmosphere and, crucially, should have the same level of persistence. But when he checked this assumption using data on CO2 levels and lower tropospheric temperatures as measured by the University of Alabama in Huntsville satellite record, he found that CO2 levels have a unit root but temperatures do not. Specifically they have relatively little persistence. Which doesn’t make sense if CO2 is the control knob since in that case whatever CO2 does, including persist, should cause temperatures to do the same.

Hartley says his results imply there is something else at work driving temperatures that offsets the effect of CO2. So he thinks CO2 does affect temperatures, but in combination with something else that cancels out its persistence pattern, making it not the sole control knob. Which is an interesting theory but not in his wheelhouse.

Statistics are. But since he therefore isn’t a “climate scientist” we are 100% confident his results will be ignored by the IPCC and climate experts, and if any of them do look at it they may well not understand it. Because the question he is investigating requires advanced statistical training and they’re not, ahem, experts.

That Hartley could not find a relationship between CO2 and temperature is hardly surprising as the Green House Effect does not exist as it violates the 1st & 2nd Laws of Thermodynamics. All CDN readers should familiarize themselves with the work of Nikolov and Zeller. NZ, who are physicists not climate scientists, neatly explain both long and short term climate temperature variations using data from NASA. They show that short term variations are largely due to variations in cloud albedo and millennial changes are due to variations in atmospheric pressure. Their work is seminal in my opinion but because it goes against the ruling paradigm will take a long time to be accepted.

Two facts that are usually ignored in climate science are firstly that 98% of the CO2 on the Earth’s surface is in solution in the oceans while only 2% is in the atmosphere, and secondly that the solubility of CO2 in seawater has an inverse relationship with temperature. One can therefore postulate two different temperature/CO2 relationships:

1. CO2 drives temperature. This is the ‘standard’ theory which seems to take very little notice of oceanic effects.

2. Temperature drives CO2. As temperature increases, for reasons other than atmospheric CO2 levels, the oceans will warm. Since the solubility of CO2 decreases with temperature the oceans will then vent CO2 into the atmosphere and the atmospheric level of CO2 will rise accordingly. Incidentally, CO2 levels are known to decrease drastically during an ice age because, presumably, CO2 solubility increases as the oceans cool so it is sucked out of the atmosphere.

You choose.

This qualifies for the usual one dumb article per week.

The monthly change in the global average temperature is the net sum of every climate change variable. Rising CO2 emissions cause global warming, but they are not the only cause. You can prove that CO2 is an important global warming variable by simply looking at 10 year increments from 1975 to 2025 (1975 to 1985, 1985 to 1995, etc.). Total CO2 emissions over 10 years has a very strong positive correlation with total global average warming over the same 10 year period. Both variables have also been accelerating since 1975.

Then there's the opinion of the founder of the Climate Crisis Advisory Group, Sir David King, https://english.elpais.com/climate/2025-12-31/david-king-chemist-there-are-scientists-studying-how-to-cool-the-planet-nobody-should-stop-these-experiments-from-happening.html. Like most media, El Pais is heavily invested in climate catastrophe

CO2 is both a (1) climate forcing and (2) a climate feedback at the same time.

As a climate forcing, man made CO2 emissions are a strong and fast acting variable

As a climate feedback, CO2 is a very small and slow acting climate variable.

You seem to be fooled by the either or (False Dilemma) logical error. You falsely believe that CO2 cannot be a climate forcing and climate feedback at the same time. There are two more very long term CO2 processes happening at the same time:

(3) The process of CO2 being sequestered as calcium carbonate on the ocean floor is part of a climate feedback, specifically involving the "oceanic carbon pump".

(4) Higher temperatures and rainfall (due to more CO2) and speeds up chemical reactions between rainwater and silicate rocks (AKA rock weathering), global warming causes rocks to weather faster, but the effect on \(CO_{2}\) depends on the type of rock being weathered. While most weathering acts as a "sink" that removes \(CO_{2}\) from the air, some specific processes actually release it. The science is not settled on this subject. What are a list of every climate related process involving CO2 ranging from months to millions of years?

https://www.google.com/search?q=What+are+a+list+of+every+climate+related+process+involving+CO2+ranging+from+months+to+millions+of+years

But Richard, aren't we often told that correlation is not causation?